The foundations of the I Ching

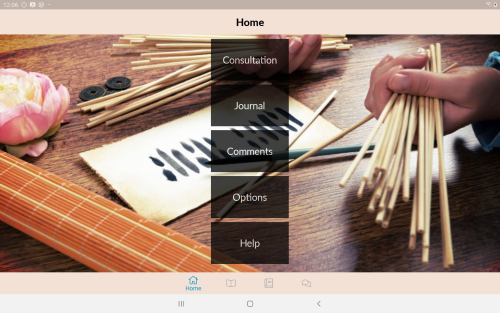

This page is a quick introduction to the principles of the I Ching.

Yin and Yáng

The Yin and the Yáng are the two founding principles of the Tao. The Yin is represented by the Chinese ideogram 陰 and designs clouds or the shady side of the mountain. As for the Yáng , it is represented by the ideogram 陽 and designates light or the sunny side of the mountain.

In the I Ching, the Yin is drawn with a dotted line, it also correspond to the number 2.

- Returning home

- To rest

- To close

The Yáng is drawn with a continuous line, it is associated with the number 3.

- Going outside

- To act

- To continue

The trigrams

The combination of three yin or yáng lines creates a trigram. The possibilities are:

| Wilhelm, Baynes | The creative, heaven | |

|---|---|---|

| Taoscopy | Eternity |

| Wilhelm, Baynes | Keeping still, mountain | |

|---|---|---|

| Taoscopy | Restraint |

| Wilhelm, Baynes | The clinging, fire |

|---|---|

| Taoscopy | The sending |

| Wilhelm, Baynes | The gentle, wind, wood |

|---|---|

| Taoscopy | The answer |

| Wilhelm, Baynes | The receptive, earth |

|---|---|

| Taoscopy | The matter |

| Wilhelm, Baynes | The arousing, thunder |

|---|---|

| Taoscopy | The rule |

| Wilhelm, Baynes | The abysmal, water |

|---|---|

| Taoscopy | Hygiene |

| Wilhelm, Baynes | The joyous, the lake |

|---|---|

| Taoscopy | The overflow |

The trigrams names used here match the designations found in the book of Richard Wilhelm, translated by Cary F. Baynes and those of this site. The invention of the trigrams is attributed to the legendary ruler Fuxi.

The hexagrams

Two trigrams combine to form an hexagram. There are sixty-four possibilities. The hexagrams can be studied here.

Here is for example the hexagram 53 which means "To associate".

As you may have noticed already, this hexagram's lower trigram is:

and the upper trigram is:

The "answer" to "restraint" is clearly "association".

The origin of the hexagrams is not precisely known. They have been mentioned in the Lian Shan at the time of Yu the Great, between 2200 and 2100 BC.

The I Ching is a book whose purpose is to explain the hexagrams. As such, many elements are to consider. The most recent translations of these texts are not in the public domain, so we'll have to be satisified with their description. You can find them in Richard Wilhelm's book translated in English by Cary F. Baynes.

The turtle shells

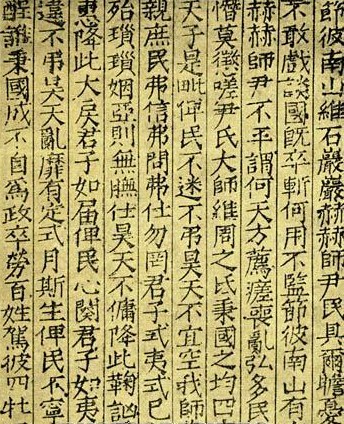

Some of the comments of the I Ching have been found on turtle shells which were used for divination. So, their origin would be older than the authors that are traditionally designed.

The judgements

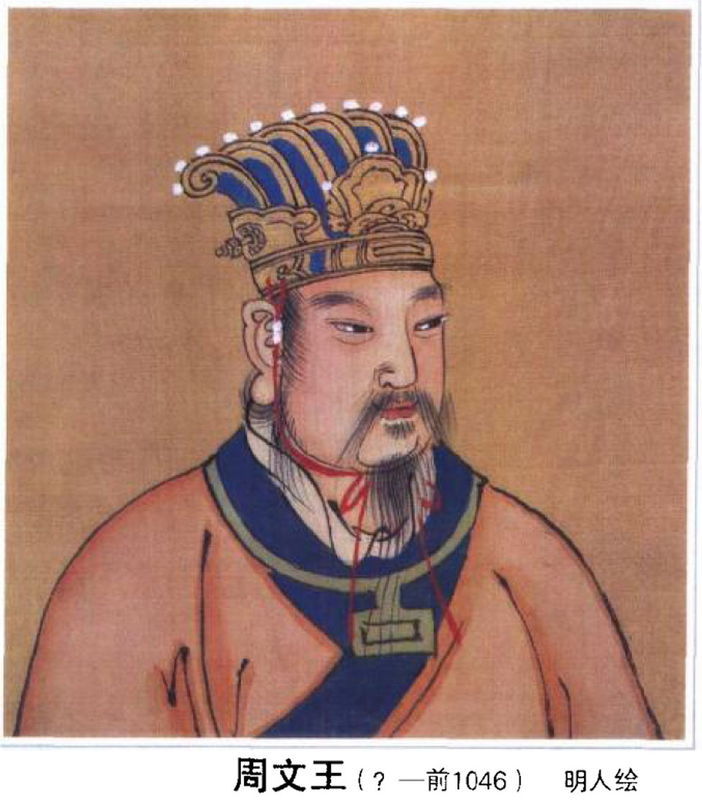

The judgements according to the tradition have been written or compiled by the King Wen of Zhou (~1152 to ~1056 BC) during a period of captivity. They give an advice related to the situation described by the hexagram.

The images

The comments on the images are attributed to Confucius (551 to 479 BC). They give a precise indication on the conduct to follow in accordance with the hexagram. Confucius tells us about the superior man (also called the noble man or the cultivated man) who is taking advantage of the hexagrams teachings to progress.

The comments on the lines

These comments were, again according to the tradition, compiled or written by the Duke of Zhou (? to 1032 BC), son of the King Wen. The lines are the six Yin or Yàng elements which form an hexagram. They are readen from the bottom to the top and they are numbered from 1 to 6. The comments on the lines are very useful when studying the changes.

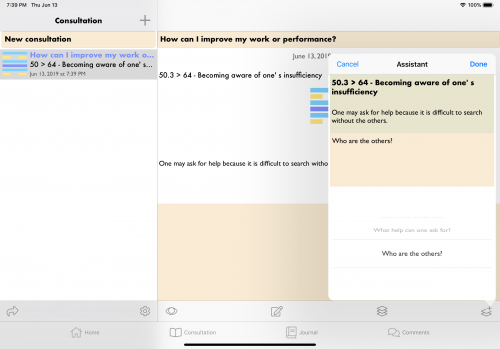

Taoscopy's comments

Those are in the public domain. You will find them on this site and you can obtain a copy here.